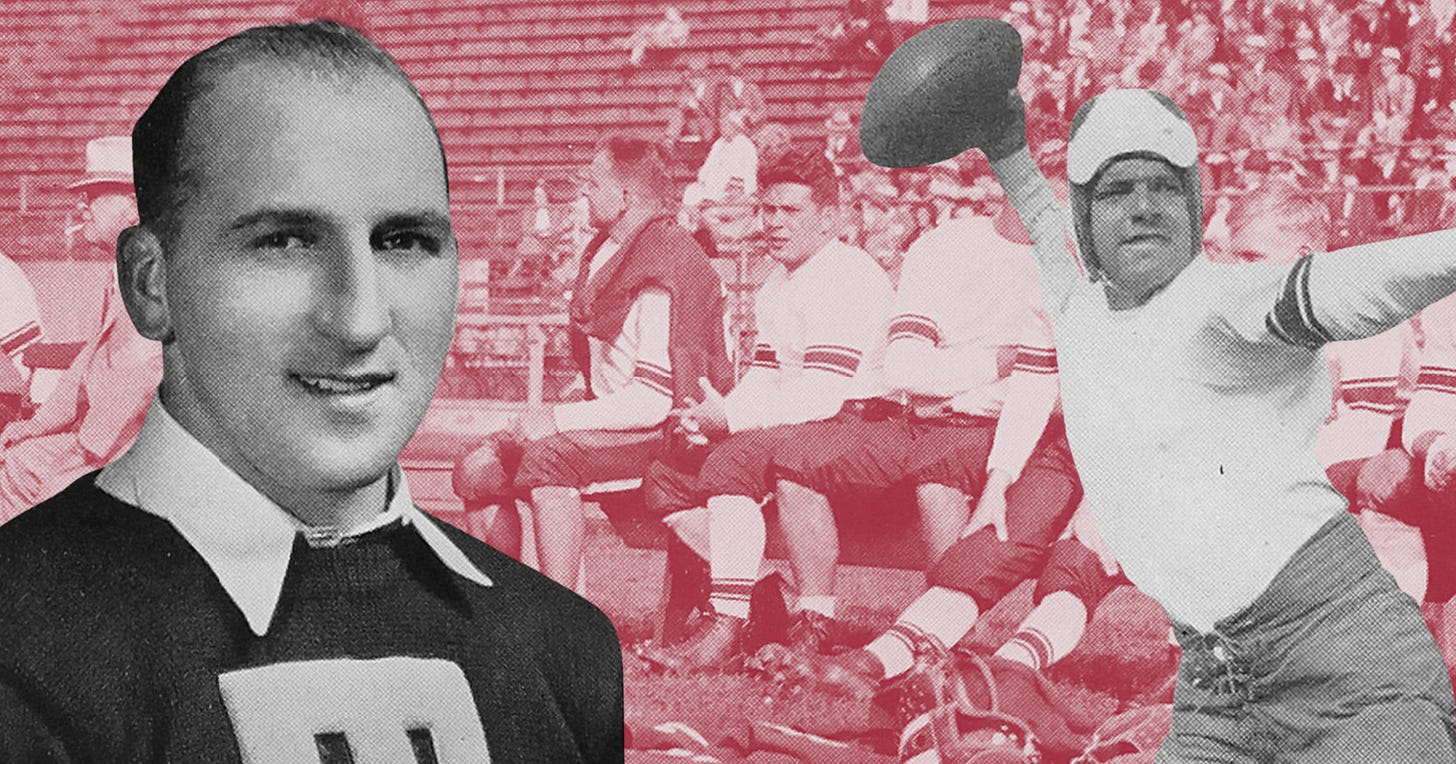

Pete Stevens and John Stonik: Two Plymouth boys who made good at Temple

Legendary coach Glenn "Pop" Warner advocated for Stevens' All-America selection and elected him Temple captain.

John “Stumpy” Stonik and Pete Stevens were once two boys with a shared dream and love for football.

Stonik, of East Main Street, and Stevens, of Nesbitt Alley, grew up less than 2 miles from each other in Plymouth, Luzerne County. Stonik, a member of the Plymouth High School Class of 1928, was six months older than Stevens, Class of ’29.

They’d grow together, then apart, then reunite and separate again, all the while achieving major success and writing their names into college football history.

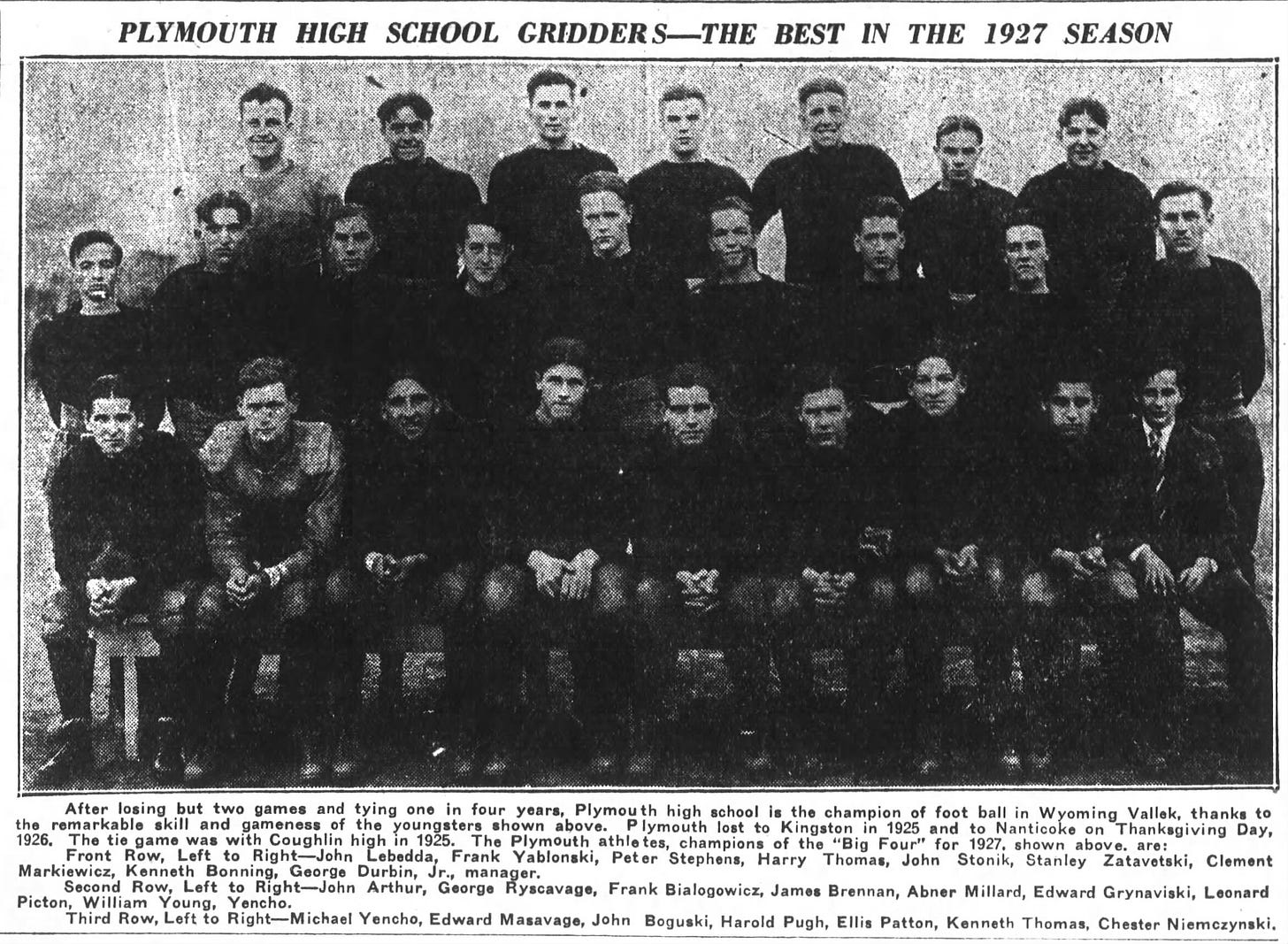

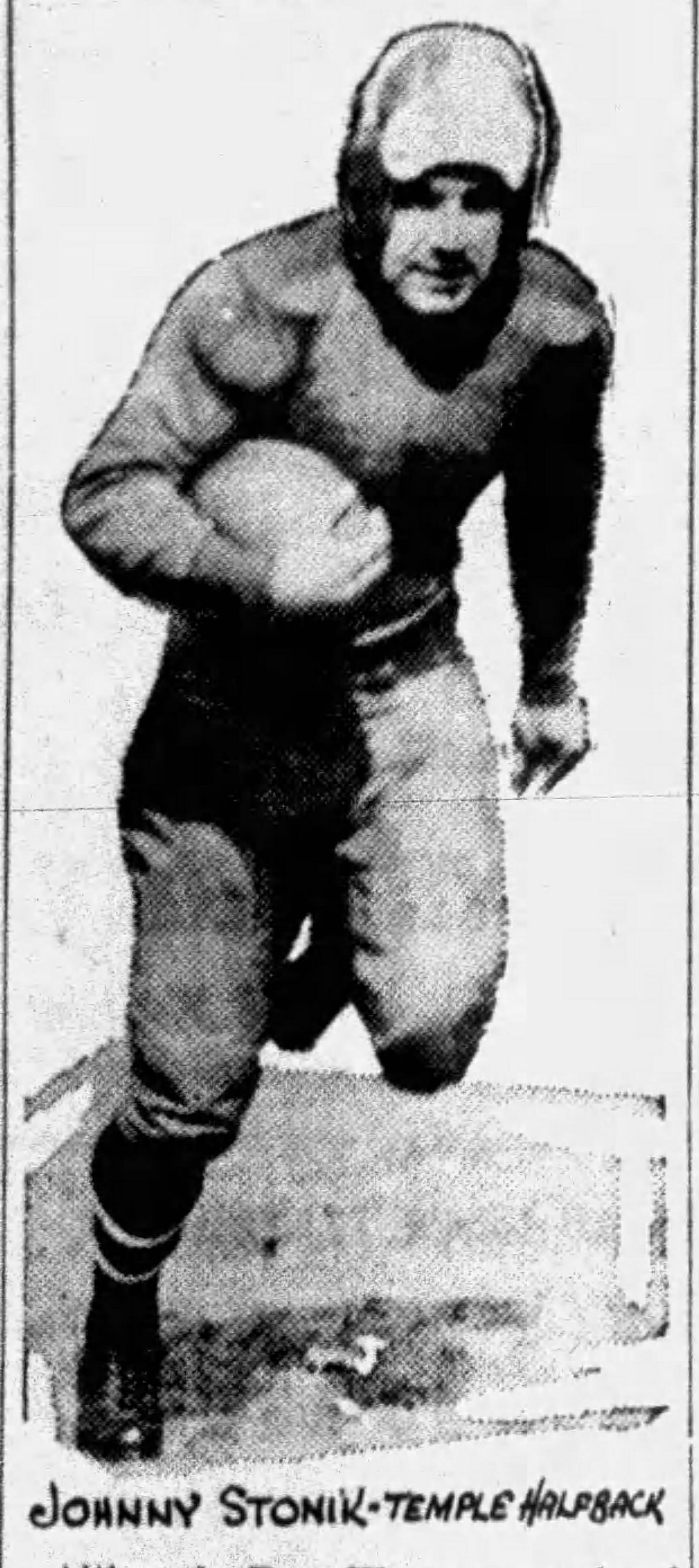

The elder Stonik was the starting fullback and captain when Plymouth won the 1927 Wyoming Valley league championship with an undefeated, untied record. He was a tough kid who begrudgingly wore headgear and was accused (and cleared, at least in the local media) of throwing punches between plays.

Stonik’s graduation devastated Plymouth. He was, after all, “one of the most outstanding backs ever produced in Wyoming Valley scholastic grid history,” the Wilkes-Barre Record said.

Meanwhile, Stevens, the starting center, was a fine high school player. Unlike Stonik, however, he was not a star, although it never discouraged them from their shared dream.

“Johnny and Pete had fully decided that when it came time for college, they would go together,” the Evening News reported. “For a time, it looked as if there would be a hitch.”

Several hitches.

For one, Stonik was older. Secondly, Stonik had considerably more interest from college recruiters. Thirdly, Stonik chose to prep for a year at Montgomery School in Philadelphia. Stevens, a year later, also went the prep school route at Roxbury School in Massachusetts.

But finally, in 1931, four years after making high school history, Stonik and Stevens were reunited in Philadelphia. They were Temple Owls.

Playing for head coach Heinie Miller, a three-time All-American at the University of Pennsylvania, Stonik and Stevens were reserves in 1931. They saw the field some in 1932.

Then, something incredible happened. For Stonik. For Stevens. For Temple.

Temple landed Glenn “Pop” Warner, 61, as head football coach. Warner, an East Coast native who’d coached Jim Thorpe at Carlisle Indian School and won multiple national championships at the University of Pittsburgh, had grown unhappy in his position at Stanford and bolted back to Pennsylvania.

“Too much alumni interference, too much attempt by the ‘wolves,’ who are former Stanford graduates, to dictate the policy of football, are the reasons why Warner … quit the post,” said the San Francisco Chronicle’s Harry B. Smith.

Warner insisted he took the Temple job because he felt it was a promotion.

“From what I have learned about Temple, it is a growing institution which has been rapidly coming to the front in an educational way,” Warner wrote to the Philadelphia Inquirer. “I see no reason why football and other branches of athletics should not flourish and reach as high a stage of development there as at other large universities of the East.”

Temple tripled the head coaching salary to $15,000. Warner’s staff included a highly paid assistant, too, in Miller, who stayed with the program for the 1933 season.

Warner’s rookie season at Temple was unremarkable. The Owls went 5-3. Meanwhile, Stanford went 8-2-1 and won at reigning national champion USC, 13-7, a team against which Warner always struggled.

Nonetheless, Temple’s administration spun Warner’s debut as a success.

“The greatest (football season) the school has ever had,” declared Charles Beury, Temple president.

Beury made that remark in December 1933 at a function where, rather shockingly, Stevens was selected as the Lions Club’s Most Valuable Player of Temple.

Stevens, who played center in high school, was now a fullback. Not only that, but he was the backup fullback — to Stonik, who was the team’s leading scorer with 35 points, including the winning touchdown to beat West Virginia.

Stevens unseated Stonik, however, and started the final two games of the season. That’s right, the team MVP started only two of eight games.

Additionally, Warner had announced his own MVPs — two of them — and Stevens was not one of them.

“On the basis of football ability, leadership, fellowship and academic worth, the Lions’ committee picked Stevens, 5 feet, 11 inches and a resident of Plymouth — a town in the center of Pennsylvania’s hard-coal region, nursery of great footballers,” the Philadelphia Inquirer said.

While Stevens and Stonik both played fullback in 1933, neither did in 1934. Stevens moved back to center and Stonik to halfback.

After beating VPI, 34-0, to begin the season, a Philadelphia Inquirer reporter declared Warner’s team “looks better than any Temple gridiron machine the writer has ever seen in action.”

After drubbing Texas A&M, 40-6, Stevens was elected team captain. It was a certainty now that he had eclipsed the elder Stonik.

The following week, Temple’s first-year starting quarterback and star punter, Glenn Frey, of Tunkhannock, committed several miscues in a 6-6 tie against Indiana.

Frey retained his starting job, though, and led the Owls on a tear, improving to 7-0-2 by season’s end. In the regular season, Temple outgained opponents in rushing, 2,131 to 971 yards, and passing, 474 to 319. Stevens had an outstanding season and was selected an honorable mention All-American center by the International News Service. Warner gave his personal All-American endorsement to two of his players, Stevens and halfback Dave Smukler.

Meanwhile, Stonik, the best friend who’d always had the edge over Stevens, struggled. He scored only five points after his team-best 35 points a year earlier.

Temple was selected to play in the inaugural Sugar Bowl on New Year’s Day 1935, facing New Orleans’ hometown team Tulane.

“Tulane has everything in its favor,” a pessimistic Warner told the Philadephia Inquirer. “The weather, the home crowd, the advantage of playing in their own stadium. I am not going to say that we have given up all hopes of winning but our chances are very slim indeed.”

With Frey at quarterback, Stonik at left halfback and Stevens at center, the Wyoming Valley had three starters for Temple in the historic contest.

Outweighed about 10 pounds a man, Temple’s offensive line, anchored by Stevens, had an excellent performance and outran Tulane, 182 to 140 yards, on the ground. Stevens played the entire game, offense and defense. Stonik had his best game of the season, too. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported he scored a touchdown, but the official record gave credit elsewhere. Nonetheless, he got the ball often and, at the very least, set up several scores inside the redzone.

Temple led by two touchdowns in the second quarter when Smukler suffered an injury. Tulane roared back, winning, 20-14, and ending Stevens’ and Stonik’s Temple careers.

Stevens briefly played for the NFL’s Philadelphia Eagles before beginning his coaching career. After coaching at Ursinus, Stevens joined his alma mater Temple in 1947 as an assistant coach. He was Temple’s head coach from 1956 to ’59, going 4-28.

Stevens, 79, died in 1989.

Meanwile, Stonik also returned to his alma mater to coach — Plymouth High School, that is.

After a 5-4-1 season as head football coach at Wyoming High School, Stonik coached three seasons at Plymouth to a 25-4-1 record with two Wyoming Valley Conference titles. He went 10-4-4 in two seasons at Coughlin.

“Football was in Johnny’s blood,” longtime Wilkes-Barre Record sports writer Bob Patton wrote. “It was like losing his best friend when Stump was forced to give up coaching at Coughlin in 1953 due to ill health.”

Stonik, 53, died in 1961. The proceeding Meyers-Coughlin and Hanover-Plymouth games began with a moment of silence.

Stonik was posthumously inducted into the Luzerne County Sports Hall of Fame in 2002.

The Times Leader’s biographical sketch of Stonik in 2002 stated he “did more than any other local player to lay the groundwork for the popularity of high school football” in Luzerne County.